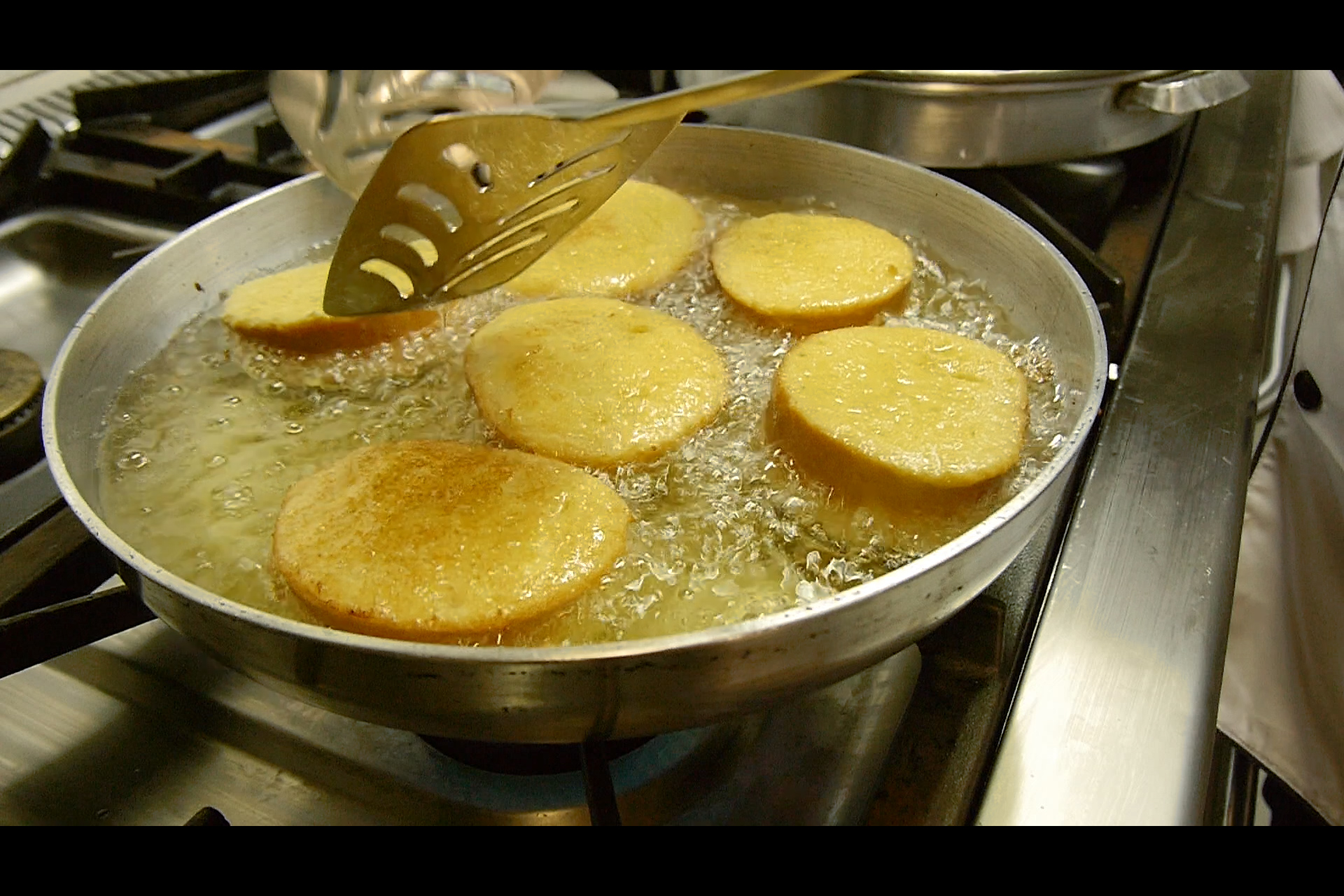

Doce de Natal por excelência, as rabanadas estão presentes de diferentes formas nas mesas dos portugueses desde há muitos séculos. O pão é embebido em leite (ou em vinho, também se admite), passa-se por ovo batido, e depois as possibilidades são várias: pode-se fritar, cozer em calda de açúcar, ou mesmo assar no forno. Em Ponte da Barca, no restaurante Sant’Ana, esta deliciosa especialidade está disponível o ano inteiro. Fui ver como se faz.

A simplicidade das rabanadas, no uso que faz do pão, já vem da antiguidade romana e a eficácia da receita explica porque se espalhou pela Europa e se manteve nos nossos hábitos gastronómicos até hoje. Neste Natal, quando estiver a fazer rabanadas, ou quando estiver a comê-las, lembre-se que está a repetir gestos que remontam a épocas que se perdem no horizonte do tempo. Tenha um Feliz Natal.

***

A typical Christmas sweet, rabanadas are present in different forms on the Portuguese people’s tables since forever. Bread is soaked in milk (or in wine), then covered in beaten eggs, and then there are many possibilities: you can fry them, boil in sugar syrup, or even roast in the oven. In Ponte da Barca, at restaurant Sant’Ana, this delicious specialty is available throughout the year. I went there to see how they make them.

The simplicity of rabanadas in the use of bread comes from Ancient Romans, and the success of the recipe explains why it spread all over Europe and why it still remains in our gastronomic habits up to today. This Christmas, as you are making rabanadas, or as you are eating them, remember that you are repeating gestures that go back to an age that fades away in the horizon of time. Merry Christmas.

The simplicity of rabanadas in the use of bread comes from Ancient Romans, and the success of the recipe explains why it spread all over Europe and why it still remains in our gastronomic habits up to today. This Christmas, as you are making rabanadas, or as you are eating them, remember that you are repeating gestures that go back to an age that fades away in the horizon of time. Merry Christmas.

PUBLICIDADE